By Adeyemi Adekunle

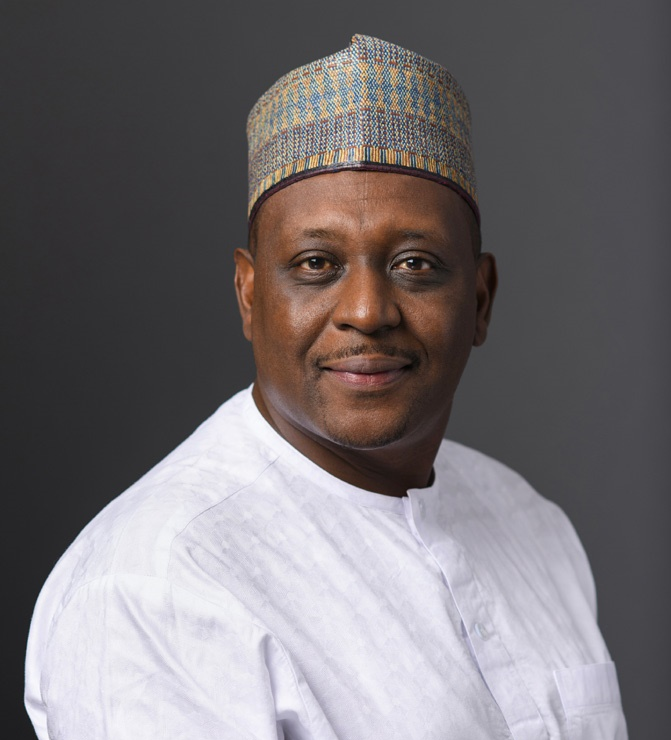

As the hum of Abuja’s bustling streets fades into the solemnity of the National Assembly, the challenges facing Nigeria’s health sector become more palpable. The Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof. Mohammed Ali Pate, stood before lawmakers today, delivering a sobering revelation during his budget defence for 2025. The figures he cited told a tale of neglect and resilience, of ambitious plans undermined by inadequate funding.

In 2024, the health ministry received a mere 15.06% of its allocated capital budget—just N26.552 billion out of the N233.656 billion promised. It wasn’t just numbers on a paper; it was a reflection of delayed projects, struggling hospitals, and a healthcare system buckling under unmet needs.

For families in rural Nigeria, it meant journeys of miles to reach under-equipped clinics. For doctors in urban centres, it meant working with broken tools in overcrowded wards. These are not just statistics but the lived realities of millions of Nigerians.

Aisha Ibrahim, a community health worker in Maru, Zamfara State shares the burden of this funding shortfall daily. “We have patients who walk hours to our clinic, only to find that basic medicines are unavailable,” she laments. “Sometimes I look at a child with malaria, knowing a simple drug could save them, and feel helpless.”

Prof. Pate’s presentation wasn’t all bleak, as he outlined a modest improvement in the proposed 2025 budget. The ministry is set to receive N10.36 billion for personnel, N1.59 billion for overhead, and N248.31 billion for capital projects—a slight boost over the previous year. Yet, optimism is tempered by a history of unmet expectations. Much of 2024’s promises were derailed by delays in accessing funds, particularly the N57.393 billion earmarked under multilateral and bilateral loans that remained inaccessible.

The minister spoke of grand visions—a health sector driven by universal health coverage, guided by the National Health Policy of 2016 and Nigeria’s Vision 20:2020. He championed the idea of a robust primary healthcare system delivering equitable, accessible, and efficient care to every Nigerian, regardless of their socio-economic status. But the reality on the ground is starkly different.

“The truth is, we have the frameworks and policies,” says Dr. Chioma Eze, a consultant physician in Lagos. “But policies don’t heal patients; timely funding and implementation do. Every time I hear these beautiful goals, I wonder how they translate to the doctor struggling to manage 80 patients in a day.”

In Prof. Pate’s vision, the 2025 budget aligns with the National Development Plan and the Sustainable Development Goals, prioritizing infrastructure, manpower, and access. He touted improvements in hospital facilities and the quality of medical training in Nigeria. “We have the required qualified manpower in the country, and that is why other countries are looking for our medical personnel,” he noted with a mix of pride and concern.

The minister’s comment about manpower rings true in part. Nigerian doctors and nurses are highly sought after globally. But that acclaim has fueled a brain drain crisis, with thousands of healthcare professionals emigrating yearly for better pay and working conditions abroad. In the wake of the minister’s words, one could not ignore the irony of world-class facilities being built while those trained to operate them leave in droves.

Within the confines of the Senate chambers, lawmakers nodded in acknowledgment as Prof. Pate spoke, their expressions a mix of concern and resignation.

Prof. Pate acknowledged these challenges, describing how strained resources have hindered progress. But he maintained that the ministry is committed to turning things around, emphasizing the need for efficient utilization of funds and alignment with federal policies to achieve tangible results.

Outside the halls of power, the sentiment is less forgiving. For residents like Adewale Ogunlana, a teacher in Ibadan whose wife recently underwent an emergency surgery at a government hospital, the disparity between political rhetoric and the reality on the ground feels personal. “We had to buy everything—syringes, gloves, drugs—for the surgery,” he recounts. “If this is what world-class healthcare looks like, then I don’t want to imagine worse.”

The burden of poor healthcare infrastructure disproportionately affects vulnerable groups—pregnant women, children, and the elderly. Bolanle Adegoke, a midwife in Oyo State, describes heart-wrenching situations where expectant mothers have died due to delays caused by inadequate resources. “We have vision statements about health for all, but here, health feels like a luxury,” she says.

Despite the criticisms, there are glimmers of hope. Non-governmental organizations and private sector collaborations continue to fill some gaps, providing much-needed support to primary healthcare centres and advocating for reforms. But these efforts cannot substitute for systemic investment.

As Prof. Pate concluded his presentation, he reiterated the government’s commitment to accelerating progress in the health sector. Whether his assurances translate into meaningful change will depend on timely funding, transparent management, and a willingness to prioritize the needs of everyday Nigerians.

The fate of Nigeria’s healthcare system lies not just in budget allocations but in the stories of the people who rely on it. For every statistic shared in the National Assembly, there’s a child waiting for life-saving vaccines, a mother hoping for safe delivery, and a doctor yearning for the tools to save lives. These stories demand more than promises; they demand action. Until that action materializes, the vision of equitable healthcare for all remains a distant dream.